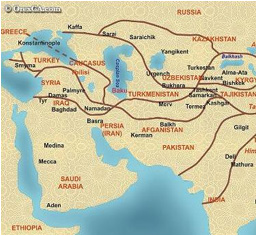

About Silk Route

The term `Silk Route' is somewhat misleading. It actually refers to various routes taken by merchants and travelers between Changan in China to various other countries in Asia, Africa, and terminating in Europe. Though it initially was a land route but sea routes were also appended to it. From its birth before Christ, through the heights of the Tang dynasty, until its slow demise six to seven hundred years ago, the Silk Route has had a unique role in foreign trade and political relations, stretching far beyond the bounds of Asia itself. It has left its mark on the development of civilizations on both sides of the continent. Though, the route has merely fallen into disuse; its story is far from over. With the latest developments, and the changes in political and economic systems, the edges of the aklamakan may yet see international trade once again, on a scale considerably greater than that of old, the modern modes of transport replacing the camels and horses of the past, the information highway replacing the messenger pigeons of the past, and the synergetic multi-cultural research replacing the warring cross-cultural suppressions.

The Silk Route was not a trade route that existed solely for the purpose of trading in silk; many other commodities were also traded, from gold and ivory to exotic animals and plants. Of all the precious goods crossing this area, silk was perhaps the most remarkable for the people of the West. For this reason, the trade route to the East was seen by the Romans as a route for silk rather than the other goods that were traded. The name `Silk Route' itself is a nineteenth century term, coined by the German scholar, von Richthofen.

Besides goods a more important and lasting item was exchanged across the Silk Route – it was religion and culture. Indians exported Buddhism, and Central Asians exported Christianity. Arabs exported Islam. Traces of intermingling of civilizations can be found in the food, culture, customs, and architecture of this region.